Pythagoreans: were a group of communities in southern Italy founded by Pythagoras. They were characterized for their rituals and their philosophical traditions. Their most famous contribution, the Pythagorean theorem, would be instrumental to the development of mathematics. This page takes information primarily from Iamblichus, an ancient Greek philosopher who wrote “De vita pythagorica” and from other sources relevant to the topic, such as the book of the elements.

A community is a group of people who share a common identity. The last four centuries have produced great advancements, unparalleled to anything known before; still, for many, specially those who are not in an “altered state of mind”, the world is in a constant state of crisis and decay. Humanity faces a crisis of skepticism, despite being in the best condition it has ever been, it doesn’t know what to do with its accumulated wealth. What is the point of producing amazing tools if they are only used to satisfy vices? For radical action to happen a person with a great vision has to emerge or an idea becomes so popular the whole society is willing to pursue it.

Pythagorean Theorem

Pythagoras most well known contribution. Since this page is dedicated to the study of the pythagoreans what better way to start than with his own theorem.

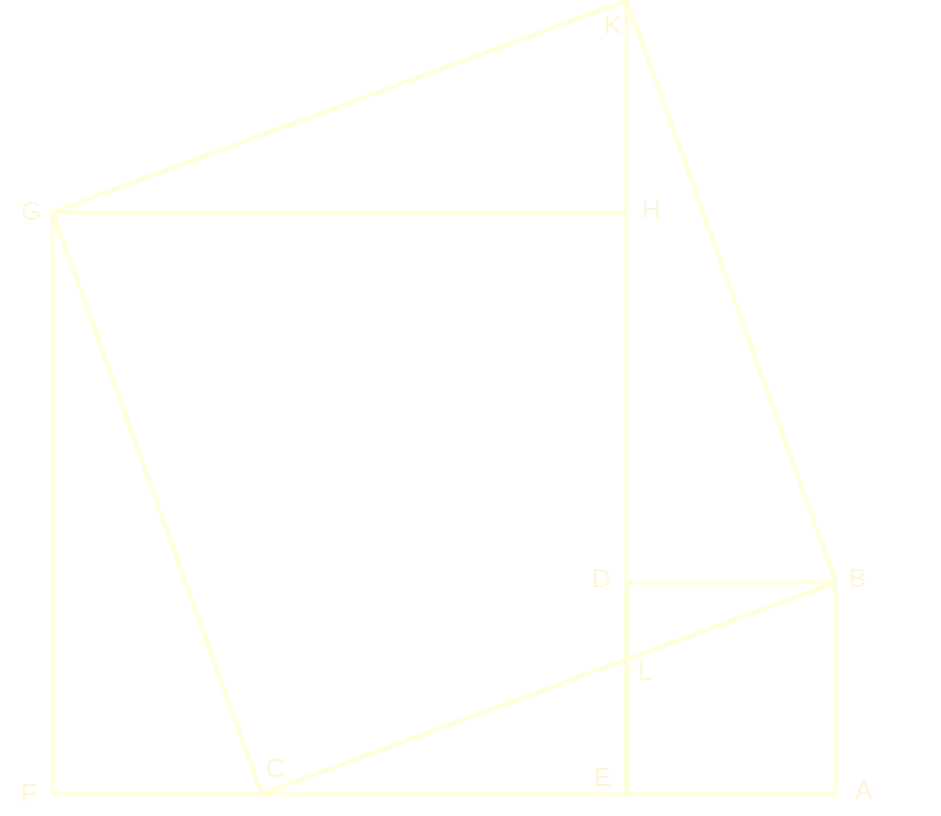

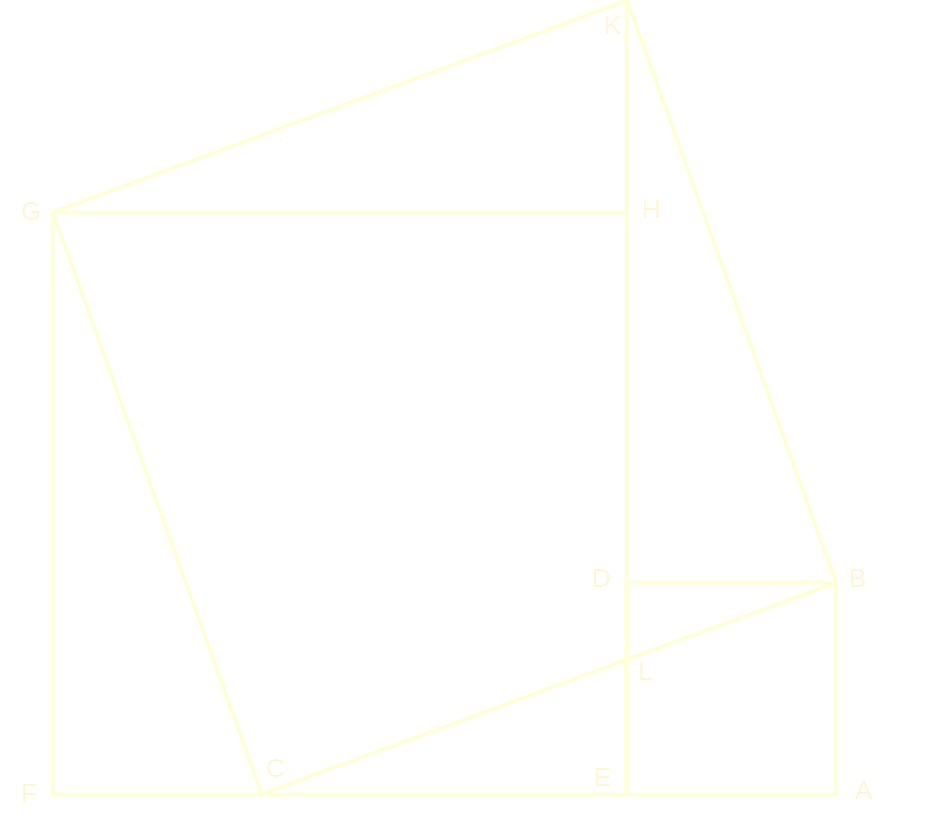

The image consist of four identical right-angle triangles: FCG, ABC, DBK and HKG. The square of the hypotenuse is the square CBKG, then from this square consider the are CBDHG and add the triangles FCG and ABC which is the same as the sum of the squares FEHG and EABD, the sides.

Euclid’s Elements Book 1

The first book of “The Elements” is intended to prove the Pythagorean theorem. But why go to such length to prove it? The above proof is already a proof, one of the earliest known proofs. While it sounds intuitive enough to be understood further examination of its elements, or components, in it will raise questions that are no longer obvious. Such as: do ‘perfect’ figures exists, even if no perfect figure can be found in nature? How can figures coincide with one another? What is a line? What is an angle? Among many other possible questions.

The problem of studying mathematics, or anything else involving an axiomatic theory, in the way presented in the elements in that it assumes that an analysis has been carried to completion. Which is to say that the axioms are the most fundamental structure that can no longer be broken down into pieces. This idea goes well in accord with a another prevalent idea dating back in time before Socrates himself: the indivisible. The indivisible “atom” as it’s name implies has no parts, hence it cannot be further divided.

Euclid’s definition of point: That which has no parts.

Yet despite a point having no parts it is still not a “nothing”. It can still act as the boundary of lines and more importantly it is the very essence of “location”. But, can it be proved that a point is the most fundamental structure? This is unfortunately up to theoretical debate.

The other problems of studying from an “atomic” perspective is that there is no clear connection between a proposition and the next one. The next proposition is expected to be obtained as a “deus ex machina” or to be provided by the author. Following a method proposed by Leibniz, which is somewhat similar to the Socratic dialogues, an existing idea should be explored by examining all its components and how they are connected to each other. If the analysis is done this way then every new layer of components in just the prior theorem and once the notions have been reduced to intuitive notions, if no contradictions arise, then the analysis is complete as intuitive notions are understood with no prior knowledge.

The approach of Leibniz fits history well, since the Pythagorean theorem was understood prior to the geometry developed to prove.

Proposition 47: In right-angle triangles the square on the side subtending the right angle is equal to the squares on the side containing the right angle.

Notions contained in the proposition:

- Right-angle triangle

- Square

- Sides of triangles and squares can coincide

- Area of two squares are equal to area of one square

Here some classifications of the terms can be made: the first two are objects, the third is the relation between objects and the last the merging of two objects into one (an operation). The last two notions already contain squares and triangles, hence right-angle triangles and squares must be explained first.

What is a triangle? A triangle has points (vertices), sides (lines) and angles. Can any any line, points and angles make a triangle. “Obviously” no, hence it must be explained how a triangle can be conceived and its underlying structure. In a similar fashion: what is s square? Notice in addition to the elements of the triangle squares need also the notion of “parallel lines”. On the third notion: no two random figures coincide, hence it must be defined what is coincidence and for the last notion what does it mean for several objects to be equal to less objects.

Structure of Book 1

- Propositions 1 – 23 describe what are the conditions for the lines, vertices and angles to make a triangle

- Propositions 24 – 26 determine how two triangles are equal to one another

- Propositions 27 – 33 describe parallel lines properties

- Propositions 34 – 45 describe parallelograms and how to determine if they are equal to one another

- Proposition 46 describes how to build a square

The notion of the parallelogram contains the notions of vertex, lines, angle and parallel. The notion of triangle contains vertex, line, angle. Last the notion of circle contains vertex and line. Since a triangle is obtained by taking the diagonal of a parallelogram it can be argued that the idea of parallelogram contains the triangle, and the triangle contains the idea of circle since for a circle it is only required a vertex and a line.

On the Common Notions

From the original proof of the Pythagorean some ideas about our intuition can be explored as well, such as considering triangles which upon displacement or rotation match each other are equal to one another. This is understood because displacement and rotation doesn’t change the “structure” of the triangle. From this the “common notion” is understood.

Common Notion 4: Things which coincide with one another are equal to one another.

The second assumption made was that taking the central area CBDHG and adding the identical pair of triangles either the large square is produced or the two smaller squares.

Common Notion 2: If equals be added to equals, the wholes are equals.

Another order of thinking goes as

- CBKG = CBDHG + DBK + HKG since DBK and HKG coincide with FCG and ABC they are equal to one another hence

- CBKG = CBDHG + FCG + ABC

- CBKG = FABDHG then on the other hand we have

- ABDE + FEHG = FABDHG

Common Notion 1: Things which are equal to the same thing are also equal to one another.

So it follows that CBKG = FABDHG and FABDHG = ABDE + FEHG then we have CBKG = ABDE + FEHG

Common Notion 3: If equals be subtracted from equals, the remainders are equals.

This can be concluded by reaching the region CBDHG either from the two squares FABDHG or the large square CBKG subtracting the corresponding the right pair of triangles.

Common Notion 5: The whole is greater than the part.

This one is understood by observing that the region FABDHG is greater than either than the sub-regions FEHG and EABD.

The commons notions are unique, and different to the postulates and definitions, in the sense that they describe our reasoning when processing the information shown in the original proof of the Pythagorean theorem. They simply can’t be demonstrated true or false. The validity of the Pythagorean theorem depends on these being true in the first place.

On the Postulates

Having determined that points, lines, incidence of lines (angles), parallel and area (region contained by lines) and plane (the space inhabited by the previous notions); it is necessary to establish how these interact with one another. Points are the “essence of location” hence their placement must be special. They can be used to delimit important parts such as highlighting the relevant portions of lines. Example: intersection of lines and center of circles. Lines themselves have the notion of endlessness, infinity, a notion which is impossible to conceive yet it is prevalent in our thoughts. One can imagine walking in a “straight” line forever, despite never happening, likewise walking along the edge of the circle could go on forever without hitting any boundary.

Postulate 1: To draw a straight line from any point to any point.

Since drawing a “straight” line first involves drawing something that is infinite, instead declare the endpoint and the draw the relevant portion of the straight line.

Postulate 2: To produce a finite straight line continuously in a straight line.

Behind every segments (bounded line) of straight lines there is in reality in reality a “infinite” straight line. So if it becomes necessary to declare any boundary outside of the segment, it is justifiable.

Postulate 3: To describe a circle with any center and distance.

This is the only “figure” (a boundary of a surface) which is assumed to exists without proof by the ancients. It a way a circle is the simplest figure, since it only require the notions of point and line. That a circle is the most fundamental figure can be justified since it cannot by conceived in parts such as triangles and squares. The outer line is build as a flux of points, similar to lines, by sliding the pencil across the surface.

Postulate 4: That all right angles are equal to one another.

This is a strange postulate considering right angle is a term pointing at a unique object. What circumstances can make two right angles be different, on a plane? This is probably due to the difficult use of common notion 4 since the segments making a right triangle can differ in size.

Postulate 5: That, if a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than two right angles.

This postulate was very troublesome for the ancients, because it seemed to provide so much information that it was believe it could be further broken down into more terms. Regardless this postulate is necessary because there has to be a way to establish which lines are parallel. Even if the definition of parallel straight lines is given on a plane how can a proposition concluding that two lines are parallel can be proven? Hence this postulate is necessary.

Last, it should be noticed that how lines and points interact with one another is left out and rather implied by the “visual” geometrical drawing. For instance it is not explained why a circle has to intersections or one with a line, or why non parallel lines only intersect at one point, etc.

Meta-Mathematical break down of the proof

Here “A” stands for “area”, “Def” for “definition”, “+” merging of two areas and “=” is to establish identity.

- A.Square + A.Square = A.Square (Pythagorean Theorem)

- Def. Square

- A.Parallelogram + A.Parallelogram = A.Parallelogram

- A.Triangle + A.Triangle = A.Triangle

- Def. Parallelogram

- Def. Parallel Lines

- Def. Triangle

- Def. Point, Def. Line, Def. Angle

In all likelihood Euclid believed his analysis had reached completion because his “fundamental particle” had no parts and could no longer be divided. At the time of the ancient Greeks “Socratic” questioning was the way to carry out analysis, so an argument would be broken into its pieces. But this could no longer be done on the point, or so he thought. Points don’t just exists on their own, they must inhabit a space and the conditions that describe the point’s existence in the plane is a whole different line of study.

Primitive Definitions

These are notion which are understood without any prior knowledge.

- A point is that which has no parts. (zero parts)

- A line is breadthless length. (length and no width, hence it only has one part or the “whole” line is its own part)

- A surface is that which has breadth and length only. (length and width, hence it has two parts)

- A boundary is that which is an extremity of anything. (The idea that a thing can be contained or isolated from the rest.)

Definitions

These are notions which are also understood without prior knowledge but require the primitive definitions.

- The extremities of a line are points. (Boundary of a line)

- The extremities of a surface are lines. (Boundary of a surface)

- A straight line is a line which lies evenly with the points on itself. The notion of straight has much been debated throughout history, it has been concluded that this is understood intuitively.

- A plane surface is a surface which lies evenly with the straight lines on itself. This and the previous definition imply each other, a plane surface could be defined by three straight lines forming a triangle.

- A plane angle is the inclination to one another of two lines in a plane which meet one another and do not lie on a straight line. And when the lines containing the angles are straight, the angle is called rectilineal. When a straight line set up on a straight lines makes the adjacent angles equal to one another, each of the equal angles is right, and the straight line standing on the other is called a perpendicular to that on which it stands. An obtuse angle is an angle greater than a right angle. An acute angle is an angle less than a right angle.

- Parallel lines are straight lines which being in the same plane and being produced indefinitely in both directions, do not meet one another in either direction.

- A figure is that which is contained by any boundary or boundaries. Here it should be pointed that even thou a segment has two points as a boundary it is typically not referred as a figure.

- A circle is a plane figure contained by one line such that all the straight lines falling upon it from one point among those lying within the figure are equal to one another. And the point is called the centre of the circle. A diameter of the circle is any straight line drawn through the centre and terminated in both directions by the circumference of the circle, and such a straight line also bisects the circle. A semicircle is the figure contained by the diameter and the circumference cut off by it. And the centre of the semicircle is the same as that of the circle.

Propositions

Notation: Implies “Imp“; Equivalent “Equiv“; to denote the sides of a triangle “S1 S2 S3“; to denote the angles of a triangle “a b c“; “S1 a S2 b S3 c” denotes, for example, the angle “a” is between the sides “S1” and “S2“, “c” in between “S1” and “S3“, etc; P[ ] CN[ ] T[ ] stand for postulate, common notion and proposition (theorem) respectively for example P[1,2] means postulate 1 and 2, this will be used to denote which notions are used to prove a proposition. A bar “|” is used the denote the end of requirements for the proposition. Addition and symbols such as “>, < and =” have their usual meaning adding and comparing magnitudes.

Proposition 25 T[4,24] Given two triangles ” S1 a S2 b S3 c ” and ” S*1 a* S*2 b* S*3 c* ” such that “ S1=S*1 ” and ” S2=S*2 ” | “ S3 > S*3 Imp a > a* ”

Proposition 24 T[4,5,19,23] Given two triangles ” S1 a S2 b S3 c ” and ” S*1 a* S*2 b* S*3 c* ” such that ” S1=S*1 ” and ” S2=S*2 ” | ” a > a* Imp S3 > S*3 “

These two propositions could be simplified to the equivalence “a > a* Equiv S3 > S*3 ” using T[4,5,19,23]

Proposition 23 T[8,22] To construct an angle equal to a given angle.

This isn’t exactly a proposition but rather a remark. These kind of propositions appear every once in a while as a way to prove that geometrical structures can be re-produced. It seems wrong doing this when superposition of figures is already used to prove propositions.

Proposition 22 T[20] Given three lengths, to construct a triangle.

This proposition along with T[20] is the fulfillment of part 7 of the meta-proof. Still, this proposition should follow T[20] as a remark or corollary.

Proposition 21 T[16,20] Given a triangle “ S1 a S2 b S3 c” with base ” S3 “. Let a line be drawn from the intersection of “ S1 ” and “ S2 ” to the base and a point be taken on the line, then draw another triangle from the base vertices to the point ” S*1 a* S*2 b* S3 c* ” | ” a* > a ”

This could become a propositional statement if the condition be that the triangles are contained within each other, but Euclid described a construction then made a claim about the angles.

Proposition 20 T[5,18] Given a triangle ” S1 S2 S3 ” | ” S1 + S2 > S3 “, ” S2 + S3 > S1 “, ” S1 + S3 > S2 “

As mentioned before this proposition is what defines a triangle and fulfill step 7 of the meta-proof.

Proposition 19 T[5,18] In any triangle ” S1 a S2 b S3 c “| ” a > b and a > c Imp S3 > S1 and S3 > S2 “

Proposition 18 T[3,16] In any triangle ” S1 a S2 b S3 c “| ” S3 > S1 and S2 > S1 Imp a > b and a > c “

Both of these propositions could be simplified to an equivalence.

Proposition 17 P[2] T[13,16] In any triangle ” S1 a S2 b S3 c ” | ” a + b < 2 Right angles “, ” b + c < 2 Right Angles “, ” c + a < 2 Right angles “

To most people nowadays this proposition seems unnecessary since we already know the sum of the interior angles of a triangle is “two right angles”, but Euclid doesn’t introduce the notion of parallel lines until proposition 26. Nevertheless it is interesting to know that Euclid could construct a triangle without the parallel lines.

Proposition 16 P[1,2] CN[5] T[3,4,10,15] Let ” d ” be the exterior angle corresponding to the side and angle ” S3″ and ” c ” | ” d > a ” and ” d > b “

Proposition 15 CN[1,3] T[13] If two straight lines cut one another the opposite angles are equal to one another.

Proposition 14 CN[1,3] T[13] If three straight lines meeting at a point make two adjacent angles equal to two right angles, the sides of the angle not adjacent make a straight line.

Proposition 13 CN[1,2] T[11] Any straight line falling on another straight line will make either two right angles or the angles will add up to two right angles.

Proposition 12 P[1,3] T[8,10] To draw a perpendicular straight line at a point on a given infinite straight line.

Proposition 11 T[1,3,8] To draw a perpendicular straight line at a point on a given straight line.

Proposition 10 T[1,4,9] To bisect a given finite straight line.

Proposition 9 T[3,8] To bisect a given rectilineal angle.

T[9] to T[15] deal with the notion of lines and how angles interact with lines.

Proposition 8 T[7] Given two triangles with ” S1 a S2 b S3 ” and ” S1 a* S2 b* S*3 c* ” | ” S3 = S*3 Imp a = a*, b=b*, c=c* “

Proposition 7 T[5] Given two straight lines, meeting at a point, drawn from the extremities of a straight line, they cannot make two different triangles on the same side.

Proposition 6 Given two triangles ” S1 a S2 b S3 c ” and ” S*1 a* S*2 b S3 c ” | ” S1 = S*1, a = a*, S*2 = S2 ”

Proposition 5 P[1,2] T[3,4] Isosceles triangles have the base angles equal to one another, and if the equal sides be equally produced further the angles under the base will be equal to one another.

Proposition 4 CN[4] Given two triangles ” S1 a S2 b S3 c ” and ” S1 a S2 b* S3* c* “| ” b = b* “, ” S3 = S3* ” and ” c=c* “

These five propositions are important because they help establish similarity between triangles.

Proposition 3 P[3] CN[1] T[2] Given two unequal straight lines, to cut off from the greater a straight line equal to the less.

Proposition 2 P[1,2,3] CN[1,3] T[1] Given a line and point to place the line on the point as an extremity.

Line operations were necessary because the mathematician could only use a compass and a straightedge, thus it was needed to describe how the straightedge can be used.

Proposition 1 P[1,3] CN[1] To construct an equilateral triangle

It is interesting to see that the equilateral triangle is the one structure that is implied by the euclidean system. This is proof that the notion of a triangle is already implicit in the system and the propositions have to be developed to reveal the structure of the triangle. This concludes the first part of the Pythagorean Theorem proof. The next set of propositions T[27] to T[33] introduce the notion of parallel lines and the parallelogram.

Brief history of Pythagoras up to his stay in Italy

His parents Mnemarchus and Pythais, were from one of the households who founded the colony in Samos. When Mnemarchus and his wife were in Delphi, the Pythia prophesied good fortune on his trip to Syria and that his pregnant wife would bear a child surpassing in beauty and wisdom those who had ever yet existed and that he would be of enormous help to the human race. Mnemarchus named his son Pythagoras after being prophesied to him by Pythian Apollo. ” No one would dispute, judging from his very birth and the all around wisdom of his life, Pythagoras’ soul was sent down to humans under Apollo’s leadership…”

Pythagoras was educated in his early age by Creophylus and Pherecydes of Syros. After his father’s death, inspired by the prophesy, he disciplined himself with religious observance, scientific studies and extraordinary regimens. “Having achieved stability of soul and mastery of body, his every word and action were accomplished with tranquility and inimitable calmness. Never overcome by anger, laughter, envy, contentiousness, or any other mental disturbance or rashness, he lived on Samos like some beneficent guardian spirit”. He left Samos when Polycrates became a tyrant and went to study from Thales, and after learning as much as he could Thales himself recommended him to learn from the priests of Egypt at Memphis and Thebes. He met Mochus of Sidon, an alleged descendant of Moses, who had formulated the atomic theory.

Taken as a prisoner to Babylon, he spent twelve years learning from the city as much as possible topics such as music, mathematics, etc. At the age of fifty six he returned to Samos. He was received by at his homeland with the same excitement as when he left, but was disappointed by his countrymen lack of interest in the symbolic way of expression he had learned in Egypt.

Eventually Pythagoras moved to Italy, he considered his fatherland to be whatever country produced the largest number of people in desire of learning. He moved to the city of Croton, Italy, where he was received by a large multitude. People were drawn to him by his cenobitic life and teachings. These were the philosophers.

On the Young People

On filial piety

A few days also after this (fishermen passage), he entered the Gymnasium, and being surrounded with a crowd of young men, he is said to have delivered an oration to them, in which he incited them to pay attention to their elders, evincing that in the world, in life, in cities, and in nature,

“That which has a precedency is more honorable than that which is consequent in time.“

Children should very much esteem their parents, to whom he asserted they owed as many thanks as a dead man would owe to him who should be able to bring him back again into light… it was indeed just to love those above all others, and never to give them pain, who first benefited us, and in the greatest degree. But parents alone benefit their children prior to their birth, and are the causes to their offspring of all their upright conduct; and that when children show themselves to be in no respect inferior to their parents in beneficence towards them, it is not possible for them in this respect to err.

For it is reasonable to suppose, that the Gods will pardon those who honor their parent in no less a degree than the divinities themselves; since we learnt from our parents to honor divinity. Hence Homer also added the same appellation to the king of the Gods; for he denominates him the father of Gods and mortals. Many other mythologists also have delivered to us, that the kings of the Gods have been ambitious to vindicate to themselves that excessive love which subsists through marriage, in children towards their parents. And that on this account, they have at the same time introduced the hypothesis of father and mother among the Gods, the former indeed generating Minerva, but the latter Vulcan, who are of a nature contrary to each other, in order that what is most remote may participate of friendship.

The judgment of the immortals is most valid.

He would demonstrate, by the example of Hercules, that it is necessary to be voluntarily obedient to the mandates of parents, as they knew from tradition that the God himself had undertaken such great labors in consequence of obeying the commands of one older than himself, and being victorious in what he had undertaken to accomplish, had instituted in honor of his father the Olympic games.

He also showed them that they should associate with each other in such

a manner, as never to be in a state of hostility to their friends, but to become most rapidly friends to their enemies; and that they should exhibit in modesty of behavior to their elders, the benevolent disposition of children towards their parents; but in their philanthropy to others, fraternal love and regard.

On temperance

… the juvenile age should make trial of its nature, this being the period in which the desires are in the most flourishing state… this alone among the virtues was adapted to a boy and a virgin, to a woman, and to the order of those of a more advanced age…

This virtue alone comprehended the goods both of body and soul, as it preserved the health and also the desire of the most excellent studies. But this is evident from the opposite. For when the Barbarians and Greeks warred on each other about Troy, each of them fell into the most dreadful calamities, through the incontinence of one man, partly in the war itself, and partly in returning to their native land. And divinity ordained that the punishment of injustice alone should endure for a thousand and ten years, predicting by an oracle the capture of Troy, and ordering that virgins should be annually sent by the Locrians into the temple of Trojan Minerva.

On erudition

Pythagoras also exhorted young men to the cultivation of learning, calling on them to observe how absurd it would be that they should judge the reasoning power to be the most laudable of all things, and should consult about other things through this, and yet bestow no time nor labour in the exercise of it; though the attention which is paid to the body, resembles depraved friends, and rapidly fails; but

Erudition, like worthy and good men, endures till death, and for some persons procures immortal renown after death.

Erudition is a natural excellence of disposition common to those in each genus, who rank in the first class of human nature. For the discoveries of these, become erudition to others. But this is naturally so worthy of pursuit, that with respect to other laudable objects of attainment, it is not possible to partake of some of them through another person, such as strength, beauty, health, and fortitude; and others are no longer possessed by him who imparts them to another, such as wealth, dominion, and many other things which we shall omit to mention.

It is possible, however, for erudition to be received by another, without

diminishing that which the giver possesses. In a similar manner also, some goods cannot be possessed by men; but we are capable of being instructed, according to our own proper and deliberate choice. And in the next place, he who being thus instructed, engages in the administration of the affairs of his country, does not do this from impudence, but from erudition. For by education nearly men differ from wild beasts, the Greeks from the Barbarians, those that are free from slaves. And in short, those that have erudition possess such as transcendency with respect to those that have not.

On citizenship and government

He was also the first that advised them to build a temple to the Muses, in order that they might preserve the existing concord. For he observed that all these divinities were called by one common name, [the Muses,] that they subsisted in conjunction with each other, especially rejoiced in common honors, and in short, that there was always one and the same choir of the Muses. He likewise farther observed, that they comprehended in themselves symphony, harmony, rythm, and all things which procure concord. They also evince that their power does not alone extend to the most beautiful theorems, but likewise to the symphony and harmony of things.

In the next place, he said it was necessary they should apprehend that they received their country from the multitude of the citizens, as a common deposit. Hence, it was requisite they should so govern it, that they might faithfully transmit it to their posterity, as an hereditary possession. And that this would firmly be effected, if they were equal in all things to the citizens, and surpassed them in nothing else than justice. For men knowing that every place requires justice, have asserted in fables that Themis has the same order with Jupiter, that Dice, i. e. justice, is seated by Pluto, and that Law is established in cities; in order that

He who does not act justly in things which his rank in society requires him to perform, may at the same time appear to be unjust towards the whole world.

It was proper that the senators should not make use of any of the Gods for the purpose of an oath, but that their language should be such as to render them worthy of belief even without oaths. And likewise, that they should so manage their own domestic affairs, as to make the government of them the object of their deliberate choice. That they should also be genuinely disposed towards their own offspring, as being the only animals that have a sensation of this conception. And that they should so associate with a wife the companion of life, as to be mindful that other compacts are engraved in tables and pillars, but those with wives are inserted in children. That they should likewise endeavour to be beloved by their offspring, not through nature, of which they were not the causes, but through deliberate choice: for this is voluntary beneficence.

They should be careful not to have connexion with any but their wives, in

order that the wives may not bastardize the race through the neglect and vicious conduct of the husbands. That they should also consider, that they received their wives from the Vestal hearth with libations, and brought them home as if they were suppliants, in the presence of the Gods themselves. And that by orderly conduct and temperance, they should become examples both to their own families, and to the city in which they live.

That besides this, they should take care to prevent every one from acting

viciously, lest offenders not fearing the punishment of the laws, should be concealed; and reverencing beautiful and worthy manners, they should be impelled to justice. He also exhorted them to expel sluggishness from all their actions; for he said that opportunity was the only good in every action.

The divulsion of parents and children from each other is to be considered

the greatest of injuries. And that

He ought to be considered as the most excellent man, who is able to foresee what will be advantageous to himself; but that he ranks as the next in excellence, who understands what is useful from things which happen to others. But that he is the worst of men who waits for the perception of

what is best, till he is himself afflicted.

Those who wish to be honored, will not err if they imitate those that are crowned in the course: for these do not injure their antagonists, but are alone desirous that they themselves may obtain the victory.

Thus also it is fit that those who engage in the administration of public

affairs, should not be offended with those that contradict them, but should benefit such as are obedient to them.

Every one who aspired after true glory, to be such in reality as he wished to appear to be to others: for counsel is not so sacred a thing as praise; since the former is only useful among men, but the latter is for the most part referred to the Gods.

And after all this he added, that their city happened to be founded by

Hercules, at that time when he drove the oxen through Italy, having been injured by Lacinius; and when giving assistance by night to Croton, he slew him through ignorance, conceiving him to be an enemy. After which, Hercules promised that a city should be built about the sepulchre of Croton, and should be called from him Crotona, when he himself became a partaker of immortality. Hence Pythagoras said, it was fit that they should justly return thanks for the benefit they had received.

On nurture

You should neither revile any one, nor take vengeance on those that reviled. Pay diligent attention to learning, which derives its appellation from age. It was easy for a modest youth to preserve probity through the whole of life; but that it was difficult for one to accomplish this, who was not naturally well disposed at a young age; or rather

It is impossible that he who begins his course from a bad impulse, should run well to the end.

Boys were most dear to divinity, and hence in times of great drought, they were sent by cities to implore rain from the Gods, in consequence of the persuasion that divinity is especially attentive to children; though such as are permitted to be continually conversant with sacred ceremonies, scarcely obtain purification in perfection.

The most philanthropic of the Gods, Apollo and Love, are universally represented in pictures as having the age of boys. It is likewise acknowledged, that some of the games in which the conquerors are crowned, were instituted on account of boys; the Pythian, indeed, in consequence of the serpent Python being slain by a boy; but the Nemean and Isthmian, on account of the death of Archemorus and Melicerta.

Apollo promised to the founder of the city of Crotona, that he would give him a progeny, if he brought a colony into Italy; from which inferring that Apollo providentially attended to the propagation of them, and that all the Gods paid attention to every age, they ought to render themselves worthy of their friendship. He added, that they should exercise themselves in hearing, in order that they may be able to speak. And farther still, that as soon as they have entered into the path in which they intend to proceed to old age, they should follow the steps of those that preceded them, and never contradict those that are older than themselves. For thus hereafter, they will justly think it right that neither should they be injured by their juniors.

On Women

In the first place indeed, as they would wish that another person who intended to pray for them, should be worthy and good, because the Gods attend to such as these; thus also it is requisite that

They should in the highest degree esteem equity and modesty, in order that the Gods may be readily disposed to hear their prayers.

In the next place, they should offer to the Gods such things as they have produced with their own hands, and should bring them to the altars without the assistance of servants, such as cakes, honey-combs, and frankincense. But that they should not worship divinity with blood and dead bodies, nor offer many things at one time, as if they never meant to sacrifice again.

With respect also to their association with men, he exhorted them to consider that their parents granted to the female nature, that they should love their husbands in a greater degree than those who were the sources of their existence. That in consequence of this, they would do well either not to oppose their husbands, or to think that they have then vanquished, when they submit to them.

It is holy for a woman, after having been connected with her husband, to

perform sacred rites on the same day; but that this is never holy, after she has been connected with any other man.

Use words of good omen through the whole of life, and to endeavor that others may predict good things of them.

He likewise admonished them not to destroy popular renown, nor to blame the writers of fables, who surveying the justice of women, from their accommodating others with garments and ornaments, without a witness, when it is necessary for some other person to use them, and that neither litigation nor contradiction are produced from this confidence,—have feigned, that three women used but one eye in common, on account of the facility of their communion with each other.

He who is called the wisest of all others, and who gave arrangement to the

human voice, and in short, was the inventor of names, whether he was a God or a daemon, or a certain divine man, perceiving that the genus of women is most adapted to piety, gave to each of their ages the appellation of some God. Hence he called an unmarried woman Core, i. e. Proserpine; but a bride, Nympha; the woman who has brought forth children, Mater; and a grandmother, according to the Doric dialect, Maia. In conformity to which also, the oracles in Dodona and at Delphi, are unfolded in to light through a woman. But through this praise pertaining to piety, Pythagoras is said to have produced so great a change in female attire, that the women no longer dared to clothe themselves with costly garments, but consecrated many myriads of their vestments in the temple of Juno.

The effect also of this discourse is said to have been such, that about the

region of the Crotonians the fidelity of the husband to the wife was universally celebrated; [imitating in this respect] Ulysses, who would not receive immortality from Calypso, on condition that he should abandon Penelope. Pythagoras therefore also observed, that it remained for the women to exhibit their probity to their husbands, in order that they might be equally celebrated with Ulysses.

On Philosophy

Pythagoras was the first who called himself a philosopher; this not being a new name, but previously instructing us in a useful manner in a thing appropriate to the name. For he said that the entrance of men into the present life, resembled the progression of a crowd to some public spectacle. For there men of every description assemble with different views; one hastening to sell his wares for the sake of money and gain; but another that he may acquire renown by exhibiting the strength of his body; and there is also a third class of men, and those the most liberal, who assemble for the sake of surveying the places, the beautiful works of art, the specimens of valor, and the literary productions which are usually exhibited on such occasions. Thus also in the present life, men of all-various pursuits are collected together in one and the same place. For some are influenced by the desire of riches and luxury; others by the love of power and dominion; and others are possessed with an insane ambition for glory.

The most pure and unadulterated character, is that of the man who gives himself to the contemplation of the most beautiful things, and whom it is proper to call a philosopher.

The survey of all heaven, and of the stars that revolve in it, is indeed beautiful, when the order of them is considered. For they derive this beauty and order by the participation of the first and the intelligible essence.

The first essence is the nature of number and reasons which pervades through all things

and according to which all these [celestial bodies] are elegantly arranged, and fitly adorned. And wisdom indeed, truly so called, is a certain science which is conversant with the first beautiful objects, and these divine, undecaying, and possessing an invariable sameness of subsistence; by the participation of which other things also may be called beautiful. But philosophy is the appetition of a thing of this kind. The attention therefore to erudition is likewise beautiful.

On Nature

The words of Pythagoras contained something of a recalling and admonitory nature, which extended as far as to irrational animals; by which it may be inferred that learning predominates in those endued with intellect, since it tames even wild beasts, and those which are considered to be deprived of reason.

For it is said that Pythagoras detained the Daunian bear which had most

severely injured the inhabitants, and that having gently stroked it with his hand for a long time, fed it with maze and acorns, and compelled it by an oath no longer to touch any living thing, he dismissed it. But the bear immediately after hid herself in the mountains and woods, and was never seen from that time to attack any irrational animal.

Perceiving likewise an ox at Tarentum feeding in a pasture, and eating among other things green beans, he advised the herdsman to tell the ox to abstain from the beans. The herdsman, however, laughed at him, and said that he did not understand the language of oxen, but if Pythagoras did, it was in vain to advise him to speak to the ox, but fit that he himself should advise the animal to abstain from such food. Pythagoras therefore, approaching to the ear of the ox, and whispering in it for a long time, not only caused him then to refrain from beans, but it is said that he never after tasted them. This ox also lived for a long time at Tarentum near the temple of Juno, where it remained when it was old, and was called the sacred ox of Pythagoras. It was also fed by those that came to it with human food.

Birds, symbols, and prodigies are the messengers of the Gods, sent by them to those men who are truly dear to the Gods.

He is said to have brought down an eagle that was flying over Olympia, and after gently stroking, to have dismissed it. Through these things, he demonstrated that he possessed the same dominion as Orpheus, over savage animals, and that he allured and detained them by the power of voice proceeding from the mouth.

On Music

The first attention which should be paid to men, is that which takes place

through the senses; as when some one perceives beautiful figures and forms, or hears beautiful rythms and melodies, he established that to be the first erudition which subsists through music, and also through certain melodies and rythms, from which the remedies of human manners and passions are obtained, together with those harmonies of the powers of the soul which it possessed from the first.

He arranged and adapted for his disciples what are called apparatus and

contrectations, divinely contriving mixtures of certain diatonic, chromatic, and euharmonic melodies, through which he easily transferred and circularly led the passions of the soul into a contrary direction, when they had recently and in an irrational and clandestine manner been formed; such as sorrow, rage, and pity, absurd emulation and fear, all-various desires, angers, and appetites, pride, supineness, and vehemence. For he corrected each of these by the rule of virtue, attempering them through appropriate melodies, as through certain salutary medicines.

In the evening, when his disciples were retiring to sleep, he liberated them by these means from diurnal perturbations and tumults, and purified their intellective power from the influxive and effluxive waves of a corporeal nature; rendered their sleep quiet, and their dreams pleasing and prophetic. But when they again rose from their bed, he freed them from nocturnal heaviness, relaxation and torpor, through certain peculiar songs and modulations, produced either by simply striking the lyre, or employing the voice.

Pythagoras, however, did not procure for himself a thing of this kind through instruments or the voice, but employing a certain ineffable divinity, and which it is difficult to apprehend, he extended his ears, and fixed his intellect in the sublime symphonies of the world, he alone hearing and understanding, as it appears, the universal harmony and consonance of the spheres, and the stars that are moved through them, and which produce a fuller and more intense melody than any thing effected by mortal sounds. This melody also was the result of dissimilar and variously differing sounds, celerities, magnitudes, and intervals, arranged with reference to each other in a certain most musical ratio, and thus producing a most gentle, and at the same time variously beautiful motion and convolution.

Being therefore irrigated as it were with this melody, having the reason of his intellect well arranged through it, and as I may say, exercised, he determined to exhibit certain images of these things to his disciples as much as possible, especially producing an imitation of them through instruments, and through the mere voice alone.

For he conceived that by him alone, of all the inhabitants of the earth, the mundane sounds were understood and heard, and this from a natural fountain itself and root.

He therefore thought himself worthy to be taught, and to learn something about the celestial orbs, and to be assimilated to them by desire and imitation, as being the only one on the earth adapted to this by the conformation of his body, through the daemoniacal power that inspired him. But he apprehended that other men ought to be satisfied in looking to him, and the gifts he possessed, and in being benefited and corrected through images and examples, in consequence of their inability to comprehend truly the first and genuine archetypes of things. Just, indeed, as to those who are incapable of looking intently at the sun, through the transcendent splendor of his rays, we contrive to exhibit the eclipses of that luminary, either in the profundity of still water, or through melted pitch, or through some darkly-splendid mirror; sparing the imbecility of their eyes, and devising a method of representing a certain repercussive light, though less intense than its archetype, to those who are delighted with a thing of this kind.

On Purification of the Soul

He conceived generally that labor should be employed about disciplines and studies, and ordained like a legislator, trials of the most various nature, punishments, and restraints by fire and sword, for innate intemperance, and an inexhaustible avidity of possessing; which

He who is depraved can neither suffer nor sustain.

He ordered his familiars to abstain from all animals, and from certain foods, which are hostile to the reasoning power, and impede its genuine energies.

He enjoined them continence of speech, and perfect silence, exercising them for many years in the subjugation of the tongue, and in a strenuous and assiduous investigation and resumption of the most difficult theorems.

He ordered them to abstain from wine, to be sparing in their food, to sleep little, and to have an unstudied contempt of, and hostility to glory, wealth, and the like: to have an unfeigned reverence of those to whom reverence is due, a genuine similitude and benevolence to those of the same age with themselves, and an attention and incitation towards their juniors, free from all envy.

On the Community

On initiation

As he prepared his disciples for erudition, he did not immediately receive into the number of his associates those who came to him for that purpose, till he had made trial of, and judiciously examined them.

- He inquired after what manner they associated with their parents, and the rest of their relatives

- He surveyed their unseasonable laughter, their silence, and their speaking when it was not proper

- What their desires were, with whom they associated, how they conversed with them, in what they especially employed their leisure time in the day, and what were the subjects of their joy and grief

- He likewise surveyed, their form, their mode of walking, and the whole motion of their body. Physiognomically also considering the natural indications of their frame, he made them to be manifest signs of the unapparent manners of the soul

When he had made trial of some one, he suffered him to be neglected for

three years, in the mean time observing how he was disposed with respect to

stability, and a true love of learning, and if he was sufficiently prepared with

reference to glory, so as to despise [popular] honor.

After this, he ordered those who came to him to observe a quinquennial silence, in order that he might experimentally know how they were affected as to continence of speech, the subjugation of the tongue being the most difficult of all victories; as those have unfolded to us who instituted the mysteries.

During this [probationary] time, however, the property of each was disposed

of in common, and was committed to the care of those appointed for this purpose, who were called politicians, economizers, and legislators.

Those who appeared to be worthy to participate of his dogmas, from the

judgment he had formed of them from their life and the modesty of their behavior, after the quinquennial silence, then became Esoterics, and both heard and saw Pythagoras himself within the veil. For prior to this they participated of his words through the hearing alone, beyond the veil, without at all seeing him, giving for a long time a specimen of their peculiar manners.

But if they were rejected they received the double of the wealth which they brought, and a tomb was raised to them as if they were dead by the homacoi; for thus all the disciples of the man were called. And if they happened to meet with them afterwards, they behaved to them as if they were other persons, but said that they were dead, whom they had modeled by education, in the expectation that they would become truly good men by the disciplines they would learn.

They also were of opinion that those who were more slow in the acquisition

of knowledge, were badly organized, and, as I may say, imperfect and barren.

If, however, after Pythagoras had physiognomically considered their form, their mode of walking, and every other motion, and the state of their body, and he had conceived good hope respecting them; after likewise the quinquennial silence, and the orgies and initiations from so many disciplines, together with the ablutions of the soul, and so many and such great purification produced from such various theorems, through which the sagacity and sanctity of the soul is perfectly ingenerated; if, after all this, some one was found to be still sluggish and of a dull intellect, they raised to such a one in the school a certain pillar and monument, (as they are said to have done to Perialus the Thurian, and Cylon the prince of the Sybarites, who were rejected by them) expelled him from the Homaco ̈ıon or auditory, loading him with a great quantity of silver and gold. For these were deposited by them in common, and were committed to the care of certain persons adapted to this purpose, and who were called Economics, from the office which they bore. And if afterwards they happened to meet with such a one, they conceived him to be any other person, than him who according to them was dead.

So great and so necessary was the attention which ought to be paid to disciplines prior to philosophy.

On social classes

He distributed them into different classes according to their respective merits. For it was not fit that all of them should equally participate of the same things, as they were naturally dissimilar; nor was it indeed right that some should participate of all the most honorable auditions, but others of none, or should not at all partake of them. For this would be uncommunicative and unjust. While therefore he imparted a convenient portion of his discourses to each, he benefited as much as possible all of them, and preserved the proportion of justice, by making each a partaker of the auditions according to his desert. Hence, in conformity to this method, he called some of them Pythagoreans, but others Pythagorists.

Having divided their names, some of them he considered to be genuine, but

he ordained that others should show themselves to be the emulators of these.

He ordered therefore that with the Pythagoreans possessions should be shared in common, and that they should always live together; but that each of the others should possess his own property apart from the rest, and that assembling together in the same place, they should mutually be at leisure for the same pursuits.

There were also with the Pythagoreans two forms of philosophy; for there were likewise two genera of those that pursued it, the Acusmatici, and the Mathematici. Of these however the Mathematici are acknowledged to be Pythagoreans by the rest; but the Mathematici do not admit that the Acusmatici are so, or that they derived their instruction from Pythagoras, but from Hippasus.

The philosophy of the Acusmatici consists in auditions unaccompanied with demonstrations and a reasoning process; because it merely orders a thing to be done in a certain way, and that they should endeavor to preserve such other things as were said by him, as so many divine dogmas. They however profess that they will not speak of them, and that they are not to be spoken of; but they conceive those of their sect to be the best furnished with wisdom, who retained what they had heard more than others.

But all these auditions are divided into three species, given by the kind of questions they ask

- What a thing is

The auditions therefore which signify what a thing is, are such as, What are the islands of the blessed? The sun and moon. What is the oracle at Delphi? The tetractys. What is harmony? That in which the Syrens subsist.

- What it especially is

But the auditions which signify what a thing especially is, are such as, What is the most just thing? To sacrifice. What is the wisest thing? Number. But the next to this in wisdom, is that which gives names to things. What is the wisest of the things that are with us, [i. e. which pertain to human concerns]? Medicine. What is the most beautiful? Harmony. What is the most powerful? Mental decision. What is the most excellent? Felicity. What is that which is most truly asserted? That men are depraved. Hence they say that Pythagoras praised the Salaminian poet Hippodomas, because he sings:

Tell, O ye Gods! the source from whence you came,

Say whence, O men! thus evil you became?

These therefore, and such as these, are the auditions of this kind. For each of these shows what a thing especially is. This however is the same with what is called the wisdom of the seven wise men. For they investigated, not what is simply good, but what is especially so; nor what is difficult, but what is most difficult; viz. for a man to know himself. Nor did they investigate what is easy, but what is most easy; viz. to do what you are accustomed to do. For it seems that such auditions as the above, are conformable but posterior in time to such wisdom as that of the seven wise men; since they were prior to Pythagoras.

- What ought, or what ought not, to be done

The auditions likewise, respecting what should or should not be done, were such as, That it is necessary to beget children. For it is necessary to leave those that may worship the Gods after us. That it is requisite to put the shoe on the right foot first. That it is not proper to walk in the public ways, nor to dip in a sprinkling vessel, nor to be washed in a bath. For in all these it is immanifest, whether those who use them are pure. Others also of this kind are the following: Do not assist a man in laying a burden down; for it is not proper to be the cause of not laboring; but assist him in taking it up. Do not draw near to a woman for the sake of begetting children, if she has gold. Speak not about Pythagoric concerns without light. Perform libations to the Gods, from the handle of the cup, for the sake of an auspicious omen, and in order that you may not drink from the same part [from which you poured out the liquor.] Wear not the image of God in a ring, in order that it may not be defiled. For it is a resemblance which ought to be placed in the house. It is not right to use a woman ill; for she is a suppliant. On this account also we bring her from the Vestal hearth, and take her by the right hand. Nor is it proper to sacrifice a white cock; for this also is a suppliant, and is sacred to the moon. Hence likewise it announces the hours. To him who asks for counsel, give no other advice than that which is the best: for counsel is a sacred thing. Labors are good; but pleasures are in every respect bad. For as we came into the present life for the purpose of punishment, it is necessary that we should be punished. It is proper to sacrifice, and to enter temples unshod. In going to a temple, it is not proper to turn out of the way; for divinity should not be worshiped in a careless manner. It is good to sustain, and to have wounds in the breast; but it is bad to have them behind. The soul of man alone does not enter into those animals, which it is lawful to kill. Hence it is proper to eat those animals alone which it is fit to slay, but no other animal whatever. And such were the auditions of this kind.

The most extended however were those concerning sacrifices, how they ought to be performed at all other times, and likewise when migrating from the present life; and concerning sepulture, and in what manner it is proper to be buried. Of some of these therefore the reason is to be assigned why they are ordered; such for instance as, it is necessary to beget children, for the sake of leaving another that may worship the Gods instead of yourself. But of others no reason is to be assigned. And of some indeed, the reasons are assumed proximately; but of others, remotely; such as, that bread is not to be broken, because it contributes to the judgment in Hades. The probable reasons however, which are added about things of this kind, are not Pythagoric, but were devised by some who philosophized differently from the Pythagoreans, and who endeavoured to adapt probability to what was said. Thus for instance, with respect to what has been just now mentioned, why bread is not to be broken, some say that it is not proper to dissolve that which congregates. For 63formerly all those that were friends, assembled in a barbaric manner to one piece of bread. But others say, that it is not proper, in the beginning of an undertaking, to produce an omen of this kind by breaking and diminishing. Moreover, all such precepts as define what is to be done, or what is not to be done, refer to divinity as their end; and every life is co-arranged so as to follow God. This also is the principle and the doctrine of philosophy. For men act ridiculously in searching for good any where else than from the Gods. And when they do so, it is just as if some one, in a country governed by a king, should reverence one of the citizens who is a magistrate, and neglect him who is the ruler of all of them. For the Pythagoreans thought that such men as we have just mentioned, performed a thing of this kind. For since God is, and is the lord of all things, it is universally acknowledged that good is to be requested of him. For all men impart good to those whom they love, and to those with whom they are delighted; but they give the contrary to good to those to whom they are contrarily disposed. And such indeed is the wisdom of these precepts.

Clarifying why many assertions had no demonstrations

Hippomedon, an Ægean, a Pythagorean and one of the Acusmatici, asserted that Pythagoras gave the reasons and demonstrations of all these precepts, but that in consequence of their being delivered to many, and these such as were of a more sluggish genius, the demonstrations were taken away, but the problems themselves were left.

Those however of the Pythagoreans that are called Mathematici, acknowledge that these reasons and demonstrations were added by Pythagoras, and they say still more than this, and contend that their assertions are true, but affirm that the following circumstance was the cause of the dissimilitude. Pythagoras, say they, came from Ionia and Samos, during the tyranny of Polycrates, Italy being then in a florishing condition; and the first men in the city became his associates. But, to the more elderly of these, and who were not at leisure [for philosophy], in consequence of being occupied by political affairs, the discourse of Pythagoras was not accompanied with a reasoning process, because it would have been difficult for them to apprehend his meaning through disciplines and demonstrations; and he conceived they would nevertheless be benefited by knowing what ought to be done, though they were destitute of the knowledge of the why: just as those who are under the care of physicians, obtain their health, though they do not hear the reason of every thing which is to be done to them. But with the younger part of his associates, and who were able both to act and learn,—with these he conversed through demonstration and disciplines. These therefore are the assertions of the Mathematici, but the former, of the Acusmatici.

On Hippasus and Geometry among the Pythagoreans

They assert that he was one of the Pythagoreans, but that in consequence of having divulged and described the method of forming a sphere from twelve pentagons, he perished in the sea, as an impious person, but obtained the renown of having made the discovery. In reality, however, this as well as every thing else pertaining to geometry, was the invention of that man; for thus without mentioning his name, they denominate Pythagoras. But the Pythagoreans say, that geometry was divulged from the following circumstance: A certain Pythagorean happened to lose the wealth which he possessed; and in consequence of this misfortune, he was permitted to enrich himself from geometry. But geometry was called by Pythagoras Historia. And thus much concerning the difference of each mode of philosophising, and the classes of the auditors of Pythagoras. For those who heard him either within or without the veil, and those who heard him accompanied with seeing, or without seeing him, and who are divided into interior and exterior auditors, were no other than these. And it is requisite to arrange under these, the political, economic and legislative Pythagoreans.

On the Appropriate Path to Erudition

Universally, however, it deserves to be known, that Pythagoras discovered many paths of erudition, and that he delivered an appropriate portion of wisdom conformable to the proper nature and power of each; of which the following is the greatest argument.

When Abaris, the Scythian, came from the Hyperboreans, unskilled and uninitiated in the Grecian learning, and was then of an advanced age, Pythagoras did not introduce him to erudition through various theorems, but instead of silence, auscultation for so long a time, and other trials, he immediately considered him adapted to be an auditor of his dogmas, and instructed him in the shortest way in his treatise On Nature, and in another treatise On the Gods.

For Abaris came from the Hyperboreans, being a priest of the Apollo who is there worshipped, an elderly man, and most wise in sacred concerns; but at that time he was returning from Greece to his own country, in order that he might consecrate to the God in his temple among the Hyperboreans, the gold which he had collected. Passing therefore through Italy, and seeing Pythagoras, he especially assimilated him to the God of whom he was the priest. And believing that he was no other than the God himself, and that no man resembled him, but that he was truly Apollo, both from the venerable indications which he saw about him, and from those which the priest had known before, he gave Pythagoras a dart which he took with him when he left the temple, as a thing that would be useful to him in the difficulties that would befal him in so long a journey.

For he was carried by it, in passing through inaccessible places, such as rivers, lakes, marshes, mountains, and the like, and performed through it, as it is said, lustrations, and expelled pestilence and winds from the cities that requested him to liberate them from these evils. We are informed, therefore, that Lacedæmon, after having been purified by him, was no longer infested with pestilence, though prior to this it had frequently fallen into this evil, through the baneful nature of the place in which it was built, the mountains of Taygetus producing a suffocating heat, by being situated above the city, in the same manner as Cnossus in Crete. And many other similar particulars are related of the power of Abaris.

Pythagoras, however, receiving the dart, and neither being astonished at the novelty of the thing, nor asking the reason why it was given to him, but as if he was in reality a God himself, taking Abaris aside, he showed him his golden thigh, as an indication that he was not [wholly] deceived [in the opinion he had formed of him;] and having enumerated to him the several particulars that were deposited in the temple, he gave him sufficient reason to believe that he had not badly conjectured [in assimilating him to Apollo]. Pythagoras also added, that he came [into the regions of mortality] for the purpose of remedying and benefiting the condition of mankind, and that on this account he had assumed a human form, lest men being disturbed by the novelty of his transcendency, should avoid the discipline which he possessed.

He likewise exhorted Abaris to remain in that place, and to unite with him in correcting [the lives and manners] of those with whom they might meet; but to share the gold which he had collected, in common with his associates, who were led by reason to confirm by their deeds the dogma, that the possessions of friends are common. Thus, therefore, Pythagoras unfolded to Abaris, who remained with him, as we have just now said, physiology and theology in a compendious way; and instead of divination by the entrails of beasts, he delivered to him the art of prognosticating through numbers, conceiving that this was purer, more divine, and more adapted to the celestial numbers of the Gods. He delivered also to Abaris other studies which were adapted to him. That we may return, however, to that for the sake of which the present treatise was written, Pythagoras endeavoured to correct and amend different persons, according to the nature and power of each.

On Discipline

Pythagoras in making trial [of the aptitude of those that came to him] considered whether they could echemuthein, i. e. whether they were able to refrain from speaking (for this was the word which he used), and surveyed whether they could conceal in silence and preserve what they had learnt and heard. In the next place, he observed whether they were modest. For he was much more anxious that they should be silent than that they should speak.

He likewise directed his attention to every other particular; such, as whether they were astonished by the energies of any immoderate passion or desire. Nor did he in a superficial manner consider how they were affected with respect to anger or desire, or whether they were contentious or ambitious, or how they were disposed with reference to friendship or strife. And if on his surveying all these particulars accurately, they appeared to him to be endued with worthy manners, then he directed his attention to their facility in learning and their memory.

He considered whether they were able to follow what was said, with rapidity and perspicuity; but in the next place, whether a certain love and temperance attended them towards the disciplines which they were taught. For he surveyed how they were naturally disposed with respect to gentleness. But he called this catartysis, i. e. elegance of manners. And he considered ferocity as hostile to such a mode of education. For impudence, shamelessness, intemperance, slothfulness, slowness in learning, unrestrained licentiousness, disgrace, and the like, are the attendants on savage manners; but the contraries on gentleness and mildness.

For those who committed themselves to the guidance of his doctrine, acted in the following manner: they performed their morning walks alone, and in places in which there happened to be an appropriate solitude and quiet, and where there were temples and groves, and other things adapted to give delight. For they thought

It was not proper to converse with any one, till they had rendered their own soul sedate, and had co-harmonised the reasoning power.

For they apprehended it to be a thing of a turbulent nature to mingle in a crowd as soon as they rose from bed. On this account all the Pythagoreans always selected for themselves the most sacred places. But after their morning walk they associated with each other, and especially in temples, or if this was not possible, in places that resembled them. This time, likewise, they employed in the discussion of doctrines and disciplines, and in the correction of their manners.

On Health of the Body

Most of them used unction and the course; but a less number employed themselves in wrestling in gardens and groves; others in leaping with leaden weights in their hands, or in pantomime gesticulations, with a view to the strength of this body, studiously selecting for this purpose opposite exercises.

Their dinner consisted of bread and honey or the honey-comb; but they did not drink wine during the day. They also employed the time after dinner in the political economy pertaining to strangers and guests, conformably to the mandate of the laws. For they wished to transact all business of this kind in the hours after dinner.

When it was evening they again betook themselves to walking; yet not singly as in the morning walk, but in parties of two or three, calling to mind as they walked, the disciplines they had learnt, and exercising themselves in beautiful studies. After they had walked, they made use of the bath; and having washed themselves, they assembled in the place where they eat together, and which contained no more than ten who met for this purpose. These, however, being collected together, libations and sacrifices were performed with fumigations and frankincense.

After this they went to supper, which they finished before the setting of the sun. But they made use of wine and maze, and bread, and every kind of food that is eaten with bread, and likewise raw and boiled herbs. The flesh also of such animals was placed before them as it was lawful to immolate; but they rarely fed on fish: for this nutriment was not, for certain causes, useful to them. In a similar manner also they were of opinion, that the animal which is not naturally noxious to the human race, should neither be injured nor slain.

After supper libations were performed, and these were succeeded by readings. It was the custom however with them for the youngest to read, and the eldest ordered what was to be read, and after what manner. But when they were about to depart, the cup-bearer poured out a libation for them; and the libation being performed, the eldest announced to them the following precepts: That a mild and fruitful plant should neither be injured nor corrupted, nor in a similar manner, any animal which is not noxious to the human race. And farther still, that it is necessary to speak piously and form proper conceptions of the divine, daemoniacal, and heroic genera; and in a similar manner, of parents and benefactors. That it is proper likewise to give assistance to law, and to be hostile to illegality. But these things being said, each departed to his own place of abode.

They wore a white and pure garment. And in a similar manner they lay on pure and white beds, the coverlets of which were made of thread; for they did not use woollen coverlets. With respect to hunting they did not approve of it, and therefore did not employ themselves in an exercise of this kind. Such therefore were the precepts which were daily delivered to the disciples of Pythagoras, with respect to nutriment and their mode of living.

On Friendship

Pythagoric precepts, and sentences which extended to human life and human opinions contains an exhortation to remove contention and strife from true friendship, and especially from all friendship, if possible. But if this is not possible, at least to expel it from paternal friendship, and universally from that which subsists with elders and benefactors. For to contend pervicaciously with such as these, anger or some other similar passion intervening, is not to preserve, [but destroy] the existing friendship. But they say it is necessary that the smallest lacerations and ulcerations should take place in friendships. And that this will be effected, if both the friends know how to yield and subdue their anger, and especially the younger of the two, and who belongs to some one of the above-mentioned orders.

It necessary that the corrections and admonitions which they called paedartases, and which the elder employed towards the younger, should be made with much suavity of manners and great caution; and also that much solicitude and appropriation should be exhibited in admonitions. For thus the admonition will become decorous and beneficial.

Faith should never be separated from friendship, neither seriously nor in jest. For it is no longer easy for the existing friendship to remain in a sane condition, when falsehood once insinuates itself into the manners of those who assert themselves to be friends. And again friendship is not to be rejected on account of misfortune, or any other imbecility which happens to human life; but that the only laudable rejection of a friend and of friendship, is that which takes place through great and incurable vice.

On Symbolic Language

The mode of teaching through symbols, was considered by Pythagoras as most necessary. For this form of erudition was cultivated by nearly all the Greeks, as being most ancient. But it was transcendently honored by the Egyptians, and adopted by them in the most diversified manner. Great attention was paid to it by Pythagoras, if any one clearly unfolds the significations and arcane conceptions of the Pythagoric symbols, and thus developes the great rectitude and truth they contain, and liberates them from their enigmatic form. For they are adapted according to a simple and uniform doctrine, to the great geniuses of these philosophers, and deify in a manner which surpasses human conception.

For those who came from this school, and especially the most ancient Pythagoreans, and also those young men who were the disciples of Pythagoras when he was an old man, viz. Philolaus and Eurytus, Charondas and Zaleucus, and Brysson, the elder Archytas also, and Aristæus, Lysis and Empedocles, Zanolxis and Epimenides, Milo and Leucippus, Alcmæon, Hippasus and Thymaridas, and all of that age, consisting of a multitude of learned men, and who were above measure excellent,—all these adopted this mode of teaching, in their discourses with each other, and in their commentaries and annotations.

Their writings also, and all the books which they published were not composed by them in a popular and vulgar diction, and in a manner usual with all other writers, so as to be immediately understood, but in such a way as not to be easily apprehended by those that read them. For they adopted that taciturnity which was instituted by Pythagoras as a law, in concealing after an arcane mode, divine mysteries from the uninitiated, and obscuring their writings and conferences with each other.

Hence he who selecting these symbols does not unfold their meaning by an apposite exposition, will cause those who may happen to meet with them to consider them as ridiculous and inane, and as full of nugacity and garrulity. When, however, they are unfolded in a way conformable to these symbols, and become obvious and clear even to the multitude, instead of being obscure and dark, then they will be found to be analogous to prophetic sayings, and to the oracles of the Pythian Apollo. They will then also exhibit an admirable meaning, and will produce a divine afflatus in those who unite intellect with erudition.

Mentioning a few of them, in order that this mode of discipline may become more perspicuous:

- Enter not into a temple negligently, nor in short adore carelessly, not even though you should stand at the very doors themselves

- Sacrifice and adore unshod

- Declining from the public ways, walk in unfrequented paths

- Speak not about Pythagoric concerns without light

On Nutrition

Since, however, nutriment greatly contributes to the best discipline, when it is properly used, and in an orderly manner, let us consider what Pythagoras also instituted as a law about this. Universally he rejected all such food as is flatulent, and the cause of perturbation, but he approved of the nutriment contrary to this, and ordered it to be used, viz. such food as composes and compresses the habit of the body. Hence, likewise, he thought that millet was a plant adapted to nutrition.

He rejected such food foreign to the Gods; because it withdraws us from familiarity with the Gods. He ordered his disciples to abstain from such food as is reckoned sacred, as being worthy of honor, and not to be appropriated to common and human utility. He likewise exhorted them to abstain from such things as are an impediment to prophesy, or to the purity and chastity of the soul, or to the habit of temperance, or of virtue. And lastly, he rejected all such things as are adverse to sanctity, and which obscure and disturb the other purities of the soul, and the phantasms which occur in sleep. These things therefore he instituted as laws in common about nutriment.

Separately, however, he forbade the most contemplative of philosophers, and who have arrived at the summit of philosophic attainments, the use of superfluous and unjust food, and ordered them never to eat any thing animated, nor in short, to drink wine, nor to sacrifice animals to the Gods, nor by any means to injure animals, but to preserve most solicitously justice towards them. And he himself lived after this manner, abstaining from animal food, and adoring altars undefiled with blood.